This case demonstrates how a two-part assignment helped senior nursing students develop and apply the AACN domains of person-centered care and interprofessional partnerships, making it suitable for pre-licensure nursing students and other health profession learners engaged in team-based care education.

INTRODUCTION

Nursing students must learn the 2021 American Association of Colleges of Nursing (AACN) domains of person-centered care and interprofessional partnerships to provide holistic, high-quality, and collaborative healthcare. The person-centered care domain emphasizes understanding and respecting each patient’s unique preferences, values, and needs, enabling nurses to deliver individualized care that enhances patient satisfaction and outcomes. The interprofessional partnerships domain equips students to work effectively within diverse healthcare teams, fostering communication, mutual respect, and shared decision-making to ensure comprehensive, coordinated care.

Mastery of these domains prepares students to tackle complex healthcare challenges, promoting patient-centered solutions and fostering a culture of collaboration and safety in clinical practice (AACN, 2021). However, implementing significant patient collaboration may be challenging. In this assignment, the students were to demonstrate both fully including the patient in the development of a goal and showing ways in which the goal may need to be modified based on patient input.

IMPLEMENTATION

Senior nursing students enrolled in an ambulatory care course at Emory University’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing completed a two-part assignment over the course of the fall semester of 2024 to demonstrate their mastery of the AACN (2021) person-centered care and interprofessional partnerships domains. The assignment’s objectives were: 1) to explore evidence-based interventions for patient and family-centered decision making among diverse populations, and 2) to synthesize approaches to care coordination and transitions across multiple settings.

To prepare students for success, the course instructors 1) lectured on person-centered care, motivational interviewing, and interprofessional partnerships; 2) engaged in discussions on these topics; and 3) hosted guest speakers who were subject matter experts in these areas. Slide decks used in the lectures are available upon request from the corresponding author.

For the assignment, students formed groups of four through self-selection. Once all students had chosen their groups, each group picked a patient from a list of eighteen case study scenarios (Appendix A). All case study scenarios were fictional and purposely created for educational use, not reflecting or containing any actual patient data.

Patient selection for case studies was operated on a first-come, first-served basis. Once a group chose a patient, no other group could select that patient to ensure that student presentations included a variety of patient circumstances, care plans, and interprofessional team members.

During part one of the assignment, each student group authored a paper detailing a care plan for their chosen patient. This portion of the assignment allowed students to demonstrate the interpretation and application tier of Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence (Miller, 1990). Students were instructed that the care plan had to include an interprofessional and patient-centered team approach, be based on verified best practices, reflect care coordination, and show how it was tailored to the patient. See Appendix B for the rubric used to score the papers.

During part two of the assignment, each student group performed a 10-minute in-class roleplay of an interprofessional team meeting in which they developed a SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, relevant, and time-bound) goal to address one issue from their patient’s care plan. This portion of the assignment allowed students to exhibit the demonstration tier of Miller’s pyramid of clinical competence (Miller, 1990).

Students were instructed that the members of the roleplay team had to include the patient, the RN care coordinator, and two healthcare professionals who best matched their patient’s scenario (e.g., social worker, pharmacist, physician, nutritionist, counselor). See Appendix C for the interprofessional team meeting scoring rubric.

At the start of each group’s role-play, course instructors provided a ‘wild card’ (an unexpected element) to the student portraying the patient. The wild cards reflected the dynamic nature of real-world situations and evaluated students’ readiness to respond to uncertainty in professional practice. See Appendix D for a list of wild cards.

After completing part two of the assignment, students were provided with a questionnaire that included three demographic items and five items related to self-confidence on a Likert scale. Participation in the questionnaire was voluntary and anonymous. Students were assured that their assignment grades would not be affected if they chose not to complete the questionnaire or opted out of having their results included in this analysis. The Emory Non-Human Subjects Research Determination form found that the questionnaire was exempt from IRB review.

RESULTS

Sixty-eight students (17 groups of 4) completed the assignment. Student groups were graded according to the rubrics in Appendix B and Appendix C. The average score on both the care plan paper and the role play exercise was 97%. Instructors noted that students excelled in selecting suitable interprofessional team members to address their patients’ issues, identifying appropriate interventions for their patients’ concerns, and recognizing social determinants of health that might affect the patients’ ability to achieve the SMART goal. Instructors also observed that students tended to read from a script during their role-play and stated the SMART goal at the outset, rather than allowing it to evolve through the patient’s input.

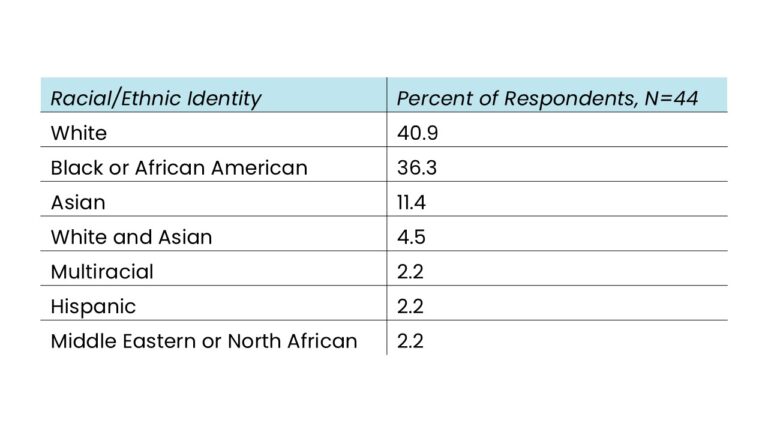

Forty-six students (67.6%) filled out the demographic and self-confidence questionnaire. Forty-four (95.6%) consented to have their results included in this analysis. The demographics of respondents showed that 88.6% were cis- or trans-women, 11.4% were cis- or trans-men, and that their average age was 26.8 years. The race/ethnicity breakdown of the participants are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Racial/Ethnic Identities of Students Completing a Person-Centered Care and Interprofessional Partnerships Assignment

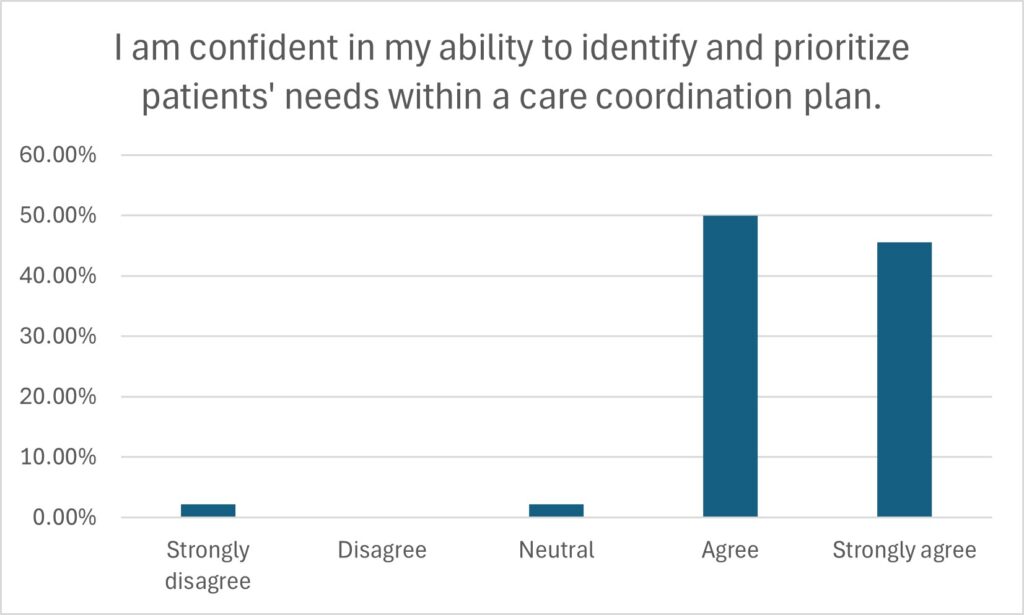

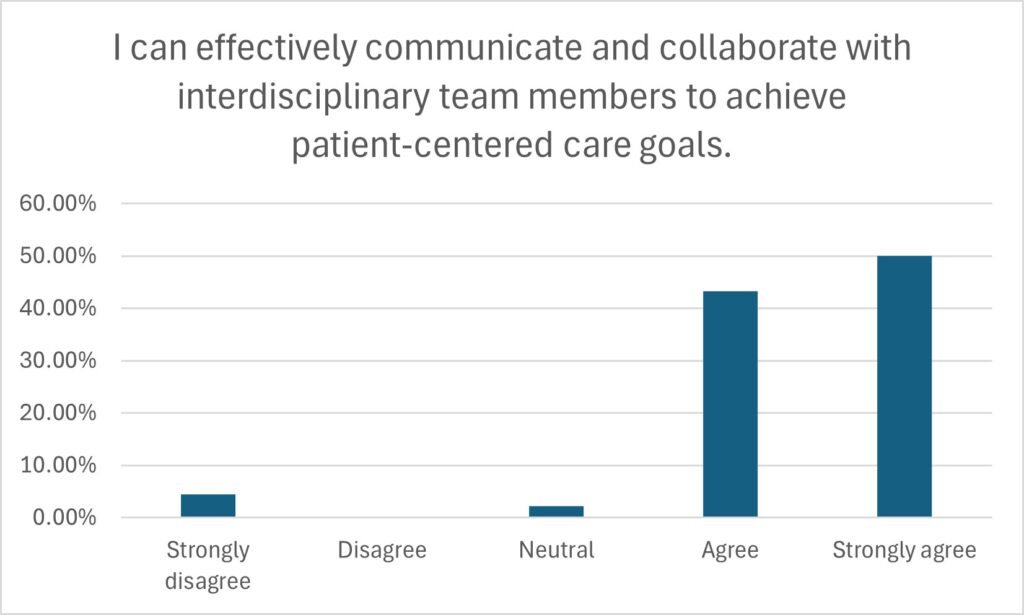

The self-confidence questionnaire results are shown in Figure 1 – results indicate a strong level of confidence among participants in their ability to identify and prioritize patients’ needs within a care coordination plan. Most participants felt confident communicating and collaborating effectively with interdisciplinary team members to achieve patient-centered care goals.

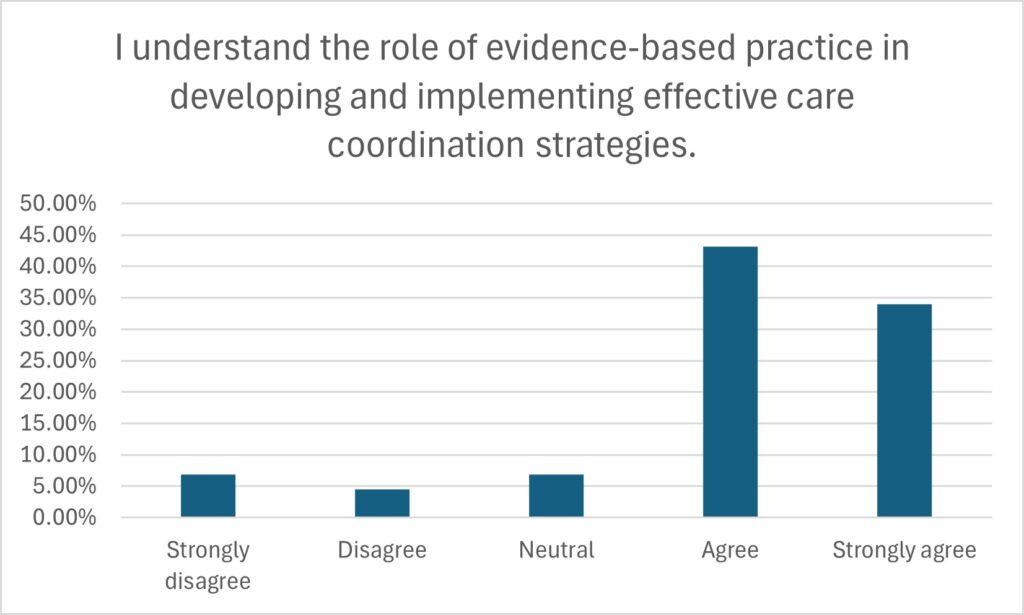

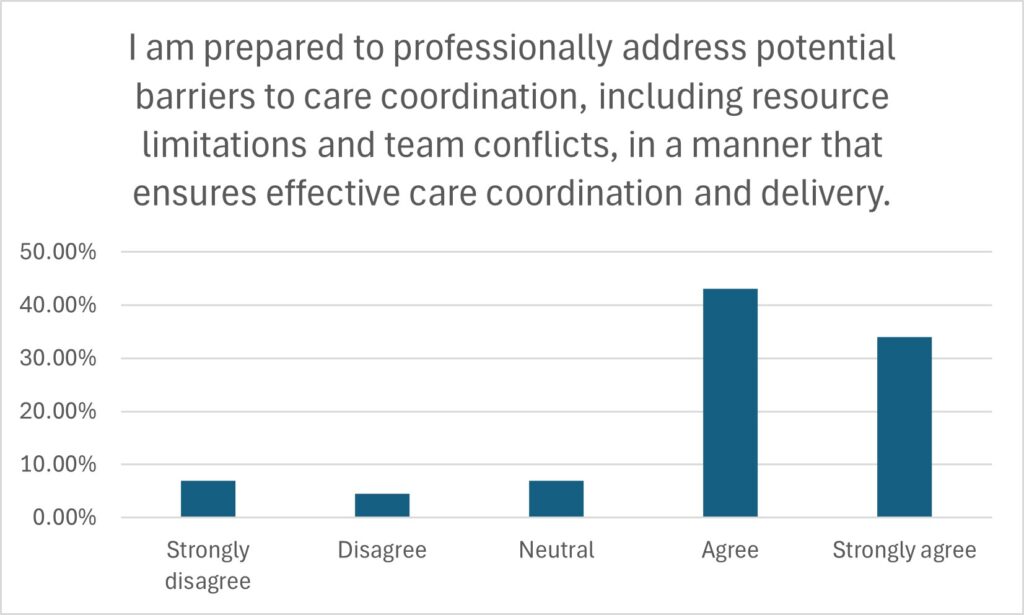

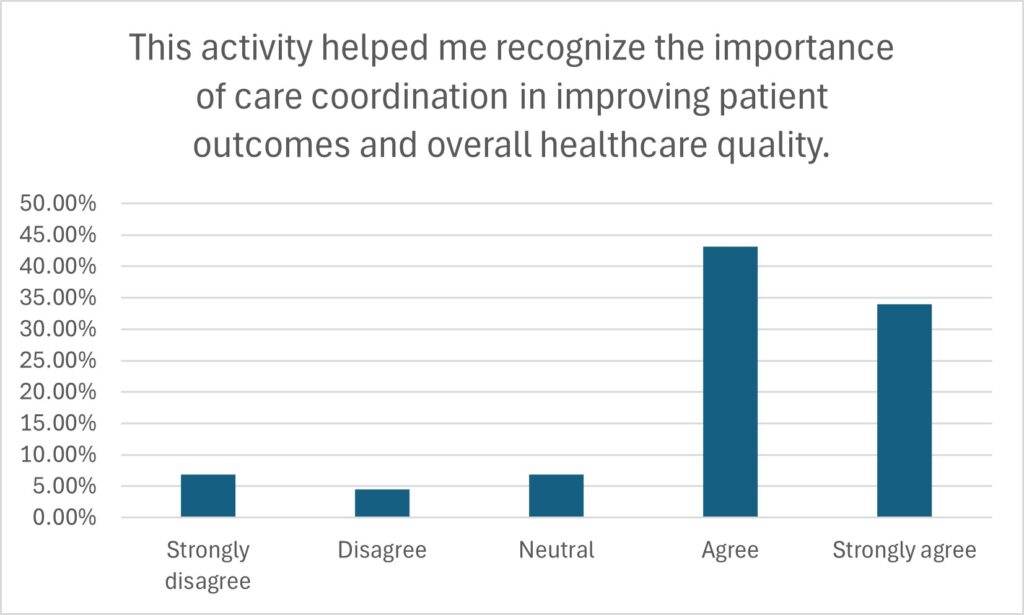

Many participants had a solid understanding of the role of evidence-based practice in developing and implementing effective care coordination strategies. The majority felt prepared to professionally address potential barriers to care coordination, such as resource limitations and team conflicts. Most participants recognized the significance of care coordination in enhancing patient outcomes and healthcare quality as a result of the activity. Overall, the findings suggest that the activity was effective in helping students understand and apply the domains of patient-centered care and interprofessional partnerships.

Figure 1: Student self-assessment after a semester-long assignment addressing patient-centered care and interprofessional relationships.

LESSONS LEARNED AND SUGGESTIONS FOR IMPROVEMENT

Survey results indicated high levels of student confidence in their ability to create a care coordination plan in collaboration with a patient partner. While these findings are encouraging, self-ratings are not always dependable, as students tend to rate themselves higher than their actual performance (Brown, 2012). Instructors observed that students performed well in the interprofessional partnership domain but may require further education or clarification in the patient-centered care domain.

In addition, full patient collaboration was not consistently demonstrated in the mock team meeting. This may reveal a limitation in student self-evaluation, as students might have overestimated their competence. In the future, a more objective assessment of student competency in patient-centered care coordination would help address this limitation.

Another area for improvement involves enhancing the realism and spontaneity of the roleplay component. Instructor observations revealed that many students relied heavily on scripted interactions and presented the SMART goal early in the exercise, rather than collaboratively developing it during the simulated interprofessional meeting. This undermines the intended emphasis on dynamic, patient-inclusive care planning.

Future iterations should include preparatory training in unscripted simulation techniques or improvisational communication to foster more authentic interactions. A faculty member could play the role of the patient and demonstrate this skill earlier in the course with volunteer students, or several faculty members could record a demonstration for students to review as an exemplar. A structured debriefing session following the roleplays could provide a reflective space to synthesize learning, receive targeted feedback, and reinforce interprofessional values.

APPLICATION ACROSS HEALTH PROFESSIONS CURRICULA

The principles of collaborative care planning, patient involvement, and interprofessional team dynamics in the assignment apply broadly across healthcare education. In fields such as medicine, physician assistant studies, pharmacy, social work, physical therapy, and public health, similar assignments can be tailored to simulate team-based case conferences, with specific roles assigned to interdisciplinary groups. For example, a medical student could serve as the lead clinician, a pharmacy student could manage medication reconciliation, and a social work student could assess resource barriers, with a standardized patient present to provide feedback.

Interprofessional education (IPE) initiatives could adopt this activity format as part of clinical skills or ethics courses. The integration of SMART goal development, role-based collaboration, and real-time problem-solving aligns with key IPE competencies, including team communication, roles and responsibilities, and values and ethics for interprofessional practice.

Incorporating this assignment into interprofessional simulation centers would enhance realism and promote cross-disciplinary collaboration. It may also serve as a capstone or summative assessment for interprofessional learning modules, providing educators with a structured way to evaluate team competencies while reinforcing holistic, patient-centered care practices.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors received no grant support for this work and declare they have no conflicts of interest in regard to this work.

American Association of Colleges of Nursing. (2021). The essentials: Core competencies for professional nursing education. https://www.aacnnursing.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Publications/Essentials-2021.pdf

Brown, J. (2012). Understanding the better than average effect: Motives (still) matter. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(2), 209–219. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167211432763

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/and performance. Academic Medicine, 65(9 Suppl), S63–S67. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045

rebekah Chance-Revels, DNP, WHNP-BC, MPH, CPH, CPSS, CPHQ

Senior Clinical Instructor, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University

Carolyn Coburn, DNP, MS, BSN, ANP-BC, APRN

Associate Professor, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University

Published 8/27/25