Co-creation of the Climate Change and Environmental Health curriculum was central to its approval and implementation and reflects the collaboration needed to address the climate crisis. A feasible tool to leverage in curricular evaluation, co-creation provides insight into factors motivating faculty to engage in Climate Change and Environmental Health education as well as pragmatic tools to support Climate Change and Environmental Health integration.

ABSTRACT

Introduction: Climate change is a human health crisis. In response, medical schools are integrating climate change and health into curricula. At our institution, we developed and implemented a disseminated Climate Change and Environmental Health preclinical curriculum through co-creation, a process in which students and faculty engage in meaningful collaboration towards a product that reflects the insights and expertise of learners and faculty.

Description of Innovation: We aimed to extend the co-creation process to evaluation of our curriculum. We carried out a multi-modal, multi-stakeholder – including students and faculty – evaluation of our Climate Change and Environmental Health curriculum. This paper presents a retrospective analysis on the reach of our Climate Change and Environmental Health curriculum complemented by faculty semi-structured interviews. Our study is among the first to incorporate faculty perspectives on the adoption and implementation of a climate and health curriculum.

Results: In the first year of implementation, our Climate Change and Environmental Health education effort engaged 35 faculty, and content was integrated in nine courses. Twenty-five out of 35 (71%) of eligible faculty participated in our survey. For curriculum leaders (N=15), the most influential factor in securing approval of the curriculum was the de facto urgency of the climate crisis (87%), followed by contextualization of content (80%) and persistence of the Climate Change and Environmental Health team (67%). Outreach by the Climate Change and Environmental Health team was cited by teaching faculty (N=13) as the most important factor for successful integration of the curriculum (62%), followed by student demand (58%). As the curriculum continues, faculty requested more networking opportunities, a Climate Change and Environmental Health education blueprint, and faculty development.

Conclusion: Faculty and administrators alike recognize the urgency of the climate crisis and the clinical implications of climate change. Climate Change and Environmental Health education efforts helped bridge personal perspectives and engagement with climate change and health in professional roles.

INTRODUCTION

Climate change is a human health crisis with implications for every medical specialty (Salas & Solomon, 2019). Direct and indirect health consequences alongside disruptions to healthcare access disproportionately affect vulnerable patients and communities (Hayden et al., 2023). Spurred by student demand and in recognition of a quickly shifting clinical reality, medical schools are integrating climate change and health into curricula (Hampshire, Islam, Kissel, Chase, & Gundling, 2022). At our institution, we created and implemented a disseminated Climate Change and Environmental Health (CCEH) preclinical curriculum and leveraged the process of co-creation as a pedagogical tool for building the curriculum (Rabin, Laney, & Philipsborn, 2020).

Approved by our curriculum committee in 2019, the pre-clinical CCEH curriculum was implemented for the class of 2024 (Rabin et al., 2020). Our co-creation approach partnered student and faculty CCEH leaders with course directors and teachers to refine and integrate CCEH (Laney, Rabin, & Philipsborn, 2022; Rabin et al., 2020). Co-creation is a recognized tool for enhancing learner and faculty engagement (Dollinger, Lodge, & Coates, 2018; Könings, Mordang, Smeenk, Stassen, & Ramani, 2021). Co-creation is also well-suited to CCEH education. Many faculty lack formal education on this emerging topic. In contrast, many incoming medical students received climate change education in their K-12 curricula or college; they are knowledgeable about and motivated to address the climate crisis. Nevertheless, students lack the clinical and medical education experience of faculty needed to apply CCEH learning to their practice of medicine. Partnership between faculty and students bridges perspectives towards productive and powerful CCEH teams.

In addition, co-creation reflects the unprecedented collaboration needed to address the climate crisis, within and across societal sectors and disciplines. The process of co-creation acknowledges the value and experience of faculty and learners, shifting a traditionally hierarchical paradigm (Stoddard, Lee, & Gooding, 2024). This paradigm shift echoes calls for physicians to partner with patients and communities in individual care plans and in the larger healthcare system (Cribb, Owens, & Singh, 2017; Israilov & Cho, 2017). Embracing co-creation, we embedded and contextualized CCEH, including content related to health equity and environmental justice, in core medical school concepts of physiology and pathophysiology.

Recognizing the importance of co-creation in the development and implementation of our CCEH curriculum, we sought to extend our co-creation approach to evaluation. To date, published evaluations of climate change and health education in undergraduate medical education (UME) are limited and generally focused on student perspectives (Gomez et al., 2021; Kligler et al., 2021; Kline et al., 2024). Fewer published efforts consider either the perspectives of the faculty leadership necessary to secure approval for such a curriculum (Blanchard, Greenwald, & Sheffield, 2023), or the multiple faculty collaborators required to implement a longitudinal curriculum. In the context of the climate crisis, multi-level perspectives in evaluation may identify opportunities to enrich learning environments, support program sustainability, and engender tandem student-faculty development towards preparing a climate-ready healthcare workforce and curricular reform (van Schaik, 2021). Faculty who engaged with CCEH curriculum approval and implementation are well-situated to provide input on factors contributing to the success of CCEH curricular efforts and opportunities to improve the co-creation process. With this in mind, we evaluated our CCEH curriculum through a multi-modal, multi-stakeholder approach that included students and faculty. Results from the student focus groups were published previously (Liu, Rabin, Manivannan, Laney, & Philipsborn, 2022); this paper presents a retrospective analysis on the reach of our CCEH curriculum complemented by semi-structured interviews of faculty.

DESCRIPTION OF INNOVATION

We assessed the reach of the CCEH pre-clinical curriculum through retrospective review of implemented content drawn from the student didactic calendar and recorded lectures. We collected data on three metrics: (1) type of content integrated (i.e., new lectures, integrated lectures, or small groups), (2) time of CCEH content engagement, and (3) faculty engagement.

Building off metric three, we conducted faculty interviews between November 2021 – April 2022. We recruited from the list of lecturers, course directors and administrators who taught a course or session targeted for CCEH co-creation, directed a preclinical course, or served in a curriculum leadership position (Supplemental Table 1). Faculty from outside our institutions were excluded from participation. We invited eligible faculty via e-mail and completed interviews via Zoom. Participation was voluntary, no compensation was provided, and interviews ranged from 10-30 minutes.

Our semi-structured interview included 14 categorical questions with optional open-ended responses. The questionnaire elicited faculty perspectives of CCEH in medical education and the local curricular effort, including factors that led to its success and opportunities for improvement. Finally, the questionnaire assessed if the CCEH curriculum influenced other areas of faculty teaching, research, or clinical practice.

Results were analyzed using descriptive statistics and qualitative thematic analysis. Of note, per Emory University Institutional Review Board (IRB), ethics approval was not required for this curricular evaluation.

RESULTS

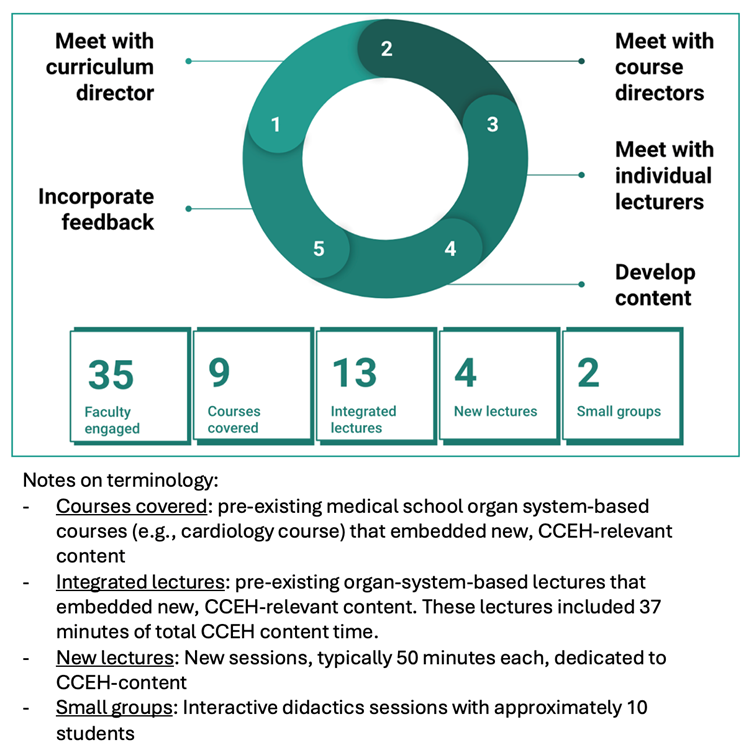

Our retrospective review of CCEH in the pre-clinical curriculum found that in the first year of the disseminated curriculum (2020-2021), CCEH content was integrated in nine courses, including four new lectures with CCEH as the central focus, plus contextualized content in 13 lectures and two small group activities (Fig 1) prior to the start of faculty evaluations. From the review of session recordings, CCEH content in the 13 integrated lectures was covered in 37 minutes total, while the new lectures took 50 minutes each for a total of 200 minutes. Each of the small group activities involved a case discussion on climate change and health.

The CCEH team engaged 35 faculty in the approval, co-creation, and implementation process. Twenty-five out of the 35 invited faculty participated in our survey for a 71% inclusion rate. Though additional faculty indicated

willingness to participate, scheduling challenges posed barriers. Participants included ten faculty who delivered content to students, 12 administrators and curriculum leaders who do not deliver content directly, and three faculty who serve in both capacities.

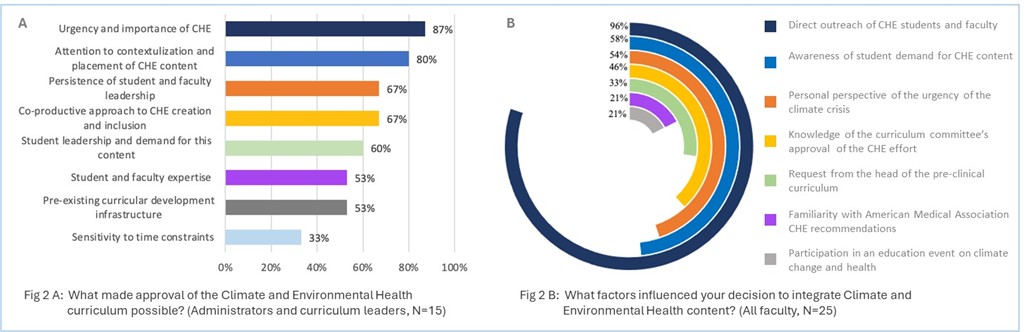

For administrators and curriculum leaders (N=15), the most influential factors in securing approval of the curriculum included the urgency of the climate crisis (87%), the attention placed on contextualization of CCEH content within the existing curriculum (80%), the persistence of student and faculty leadership (67%), the co-creation approach (67%), and student demand for the content (60%). Fewer amongst these leaders pointed to the importance of student and faculty expertise, the pre-existing infrastructure for curriculum development (both 53%) or sensitivity to time constraints (33%) (Fig 2-A). In open-ended responses, leadership acknowledged the “brilliance” of connecting the climate crisis to health for CCEH, “Not only that the world is burning and that you can do something about it but that it is relevant to your day-to-day life as a physician.” Leadership also expanded on the importance of student persistence, “The fact that you guys continued to remind and impress on how this is important to you and the class is really key…It is always easier to keep things as it is.”

In contrast, when all faculty (N=25) were asked about the most important factors for integration of CCEH, the direct outreach of the CCEH team was overwhelmingly cited as most important (96%), followed by student demand (58%), and the faculties’ own perspectives around the urgency of the climate crisis (56%). Fewer faculty (21%) pointed to recommendations by professional societies or participation in continuing medical education on CCEH as a motivation for integrating content (Fig 2-B). In open-ended responses, teaching faculty referenced that the CCEH team increased their awareness of the subject—especially as it relates to medical education—even if they were engaged in other areas of life: the “impetus was your group reaching out, and when you did, I was happy to incorporate content because I think it’s important.”

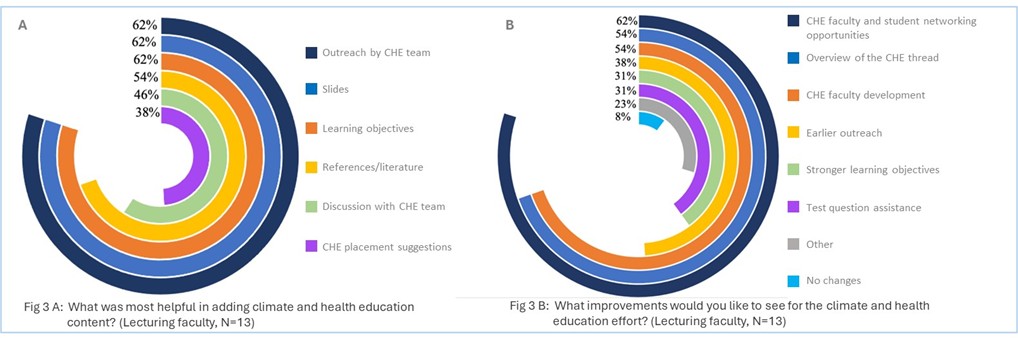

When teaching faculty (N=13) were asked what efforts of the CCEH team most effectively supported delivery of CCEH for learners, 62% selected outreach of the CCEH team, provision of slides, and provision of learning objectives (Fig 3-A). Relevant literature on the evidence-base, discussions with faculty, and potential placements for the CCEH content, were relatively less helpful, at 64%, 46%, and 38%, respectively. To improve CCEH education going forward, faculty requested faculty and student networking (62%), an overview of the broader CCEH curriculum effort (54%), and faculty development (54%) (Fig 3-B). Practical logistical support, including earlier outreach in the academic year (38%), honing learning objectives (31%), and assistance with creating test questions (31%) registered next. Themes amongst the 23% of faculty who responded with other ideas for improvement were requests for feedback on their teaching as well as opportunities for interprofessional partnerships and inclusion of learners from multiple levels of training.

When all faculty (N=25) were asked about the influence of the CCEH effort on their overall work, they indicated significant influence on other teaching endeavors (92%), with relatively less though still notable influence on advocacy (46%), clinical practice (38%), and research (29%). The preclinical curriculum provided an impetus for faculty to “be more intentional about including…content when I speak to any level learner…when I lecture to fellows for example.” Faculty described increased clinical awareness of at-risk populations and appreciation of the idea of physicians as advocates: “showing how this impacts daily work is really important.” In terms of research, faculty referenced mentorship for students and supporting faculty endeavors.

DISCUSSION

Our evaluation finds that school of medicine faculty value CCEH, recognize the urgency of the climate crisis, appreciate efforts to contextualize CCEH in the existing curriculum, and hear the persistent demand from students for CCEH education. Many faculty brought experience in medical education that helped hone a framework for content now utilized across the CCEH curriculum. Faculty perspectives suggest that co-creation resulted in a more effective and acceptable curriculum with buy-in that may help to ensure the sustainability of the CCEH effort.

Unexpectedly, leadership (87%) and teaching faculty (54%) pointed to the importance of the climate crisis in securing approval and implementation of the CCEH curriculum. Discussions on climate change at the medical school were not commonplace prior to the CCEH effort. These results suggest a latent interest in climate change and health poised for connection to day-to-day work in medicine.

Not surprisingly, contextualization of CCEH within the existing curriculum was valued by 80% of leadership respondents. Our CCEH team took painstaking efforts to avoid introducing CCEH as a new subject, and rather to employ a life-long learning lens, emphasizing the growing evidence base on the relevance of climate to existing topics in the curriculum. In this view, CCEH is essential for up-to-date coverage of concepts emphasized in preclinical training, across disciplines. That teaching faculty appreciated the provision of slides and learning objectives was also not surprising; these resources alleviate time constraints and bolster faculty CCEH knowledge.

In our view, this approach of students and faculty strategically proposing placement of CCEH with high clinical relevance, then co-creating content to be embedded within existing subjects, followed by engaging and supporting stakeholders was fundamental to our success. Although engaging so many stakeholders upfront is time-intensive initially, our integrative, disseminated approach appeared to increase buy-in and interest in the content by leadership and teaching faculty alike. In turn, this buy-in enhanced the sustainability of the effort. Applying a lens of systems change, the CCEH team acted as an accelerator to reach a tipping point of acceptance and subsequent stable integration of this content. To that end, while we continue to add new content in the medical school curriculum, maintenance of the previously-incorporated CCEH content in the pre-clinical curriculum has been much less time-intensive.

One challenge for the CCEH team going forward will be to retain our co-creation approach as the structure of the curriculum evolves. Strategies to employ innovative classroom teaching and immersive activities (in line with our student focus group discussions) may involve more learners in co-creation and retain the approach underpinning our efforts across more of the curriculum (Bovill, 2020). As shared by van Schaik, “faculty development is an essential but often underappreciated aspect of curricular reform” (van Schaik, 2021). Tools she outlines that resonated with our CCEH team and were echoed in free-responses include creating a blueprint, building on communities, encouraging co-creation and promoting collaboration.

Interestingly, the request for an overview of the CCEH curriculum and meta learning objectives—or a blueprint of design—underscores that to be effective, faculty need to know their space in the trajectory of the CCEH curriculum. This recommendation dovetails with student focus group suggestions for a CCEH framework that suits the needs of most learners (Liu et al., 2022). Faculty suggestions to grow interprofessional partnerships and to incorporate multiple levels of learners in CCEH training further underscore the collaboration required to ensure quality patient care in the climate crisis. Similarly, faculty requested faculty development and more networking with other faculty and student colleagues, which supports continued interest in co-creation more broadly. To that end, although our efforts were related to medical education, much of our approach may be helpful to those in other health professions or in graduate medical education seeking to incorporate content. In fact, activities that support awareness of the roles of other health professionals or provide CCEH education to residents-as-teachers could enrich future CCEH education for medical students.

Our study has several limitations. Interviews capture perspectives of faculty engaged with the CCEH curriculum, either by virtue of their leadership roles or because they were approached to co-create and deliver content. Their perspectives do not represent the views of all faculty or even all teaching faculty. That the interviews were conducted by the CCEH team may have led to response bias from participants. If an evaluation were to be repeated in the future, we would consider having non-CCEH team members lead the interviews. Finally, the limited number of participants and limited open-ended responses restricted our ability to undertake more sophisticated data analysis. Despite these limitations, this small number of educators proved very powerful changemakers in CCEH implementation.

CONCLUSIONS

Co-creation was an effective tool for creation and implementation of a CCEH curriculum at our institution. As an approach, co-creation supported multi-stakeholder engagement and buy-in that has ultimately differentiated our efforts and promoted the sustainability of our curriculum. Our findings will inform efforts to further co-creation and advance Emory’s CCEH education. These findings may benefit students and faculty at other institutions and in other health professions programs seeking practical tips to initiate, develop, or implement their own CCEH curriculum. Our analysis suggests that this CCEH effort helped bridge a gap between awareness of and action on the climate crisis within the scope of faculty academic roles.

| Supplemental Table 1: Characteristics of faculty interviewed for this curricular evaluation of a climate change and health Education innovation. | |

| Faculty characteristics | Percent (N= 25) |

| Specialties | Infectious diseases (3), Cardiology (3), Pulmonology (3), Neurology (2), Gastroenterology (2), Pediatrics/primary care (2), Psychiatry, Nephrology, OBGYN, Endocrinology, Rheumatology, Sports medicine, Oncology, Radiology, Pathology, Pediatrics/endocrinology |

| Faculty role | |

| Lecturer | 40% (10) |

| Non-lecturer a | 48% (12) |

| Both | 12% (3) |

| Gender | |

| Cis-female | 44% (11) |

| Cis-male | 56% (14) |

| Perceived importance of CCEH | |

| Very important | 72% (18) |

| Important | 20% (5) |

| Slightly important | 8% (2) |

| Not at all important | 0 |

| aNon-lecturer defined as course director, administrator, curricular committee representative, CCEH curricular mentor | |

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors received no grant support for this work during the initial co-creation or for the data presented in this paper. R. Philipsborn would like to acknowledge the support of the Macey Foundation, who supports the dissemination of this ongoing curricular effort. There are no conflicts of interest to declare.

Blanchard, O. A., Greenwald, L. M., & Sheffield, P. E. (2023). The Climate Change Conversation: Understanding Nationwide Medical Education Efforts. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine, 96(2), 171-184. https://doi.org/10.59249/pyiw9718

Bovill, C. (2020). Co-Creation in Learning and Teaching: The Case for a Whole-Class Approach in Higher Education. Higher Education, 79(6), 1023-1037. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00453-w

Cribb, A., Owens, J., & Singh, G. (2017). Co-Creating an Expansive Health Care Learning System. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(11), 1099-1105. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.11.medu1-1711

Dollinger, M., Lodge, J., & Coates, H. (2018). Co-Creation in Higher Education: Towards a Conceptual Model. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 28(2), 210-231. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2018.1466756

Gomez, J., Goshua, A., Pokrajac, N., Erny, B., Auerbach, P., Nadeau, K., & Gisondi, M. A. (2021). Teaching Medical Students About the Impacts of Climate Change on Human Health. The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 3, 100020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100020

Hampshire, K., Islam, N., Kissel, B., Chase, H., & Gundling, K. (2022). The Planetary Health Report Card: A Student-Led Initiative to Inspire Planetary Health in Medical Schools. The Lancet Planetary Health, 6(5), e449-e454. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2542-5196(22)00045-6

Hayden, M. H., Schramm, P. J., Beard, C. B., Bell, J. E., Bernstein, A. S., Bieniek-Tobasco, A., . . . Wilhelmi, O. V. (2023). Chapter 15. Human Health. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. Washington, DC, USA: U.S. Global Change Research Program. https://doi.org/10.7930/NCA5.2023.CH15

Israilov, S., & Cho, H. J. (2017). How Co-Creation Helped Address Hierarchy, Overwhelmed Patients, and Conflicts of Interest in Health Care Quality and Safety. AMA Journal of Ethics, 19(11), 1139-1145. https://doi.org/10.1001/journalofethics.2017.19.11.mhst1-1711

Kligler, S. K., Clark, L., Cayon, C., Prescott, N., Gregory, J. K., & Sheffield, P. E. (2021). Climate Change Curriculum Infusion Project: An Educational Initiative at One U.S. Medical School. Journal of Climate Change and Health, 4, 100065. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2021.100065

Kline, M., Malits, J., Baker, N., Shirley, H., Grobman, B., Callison, W.E, . . . Basu, G. (2024). Climate Change, Environment, and Health: The Implementation and Initial Evaluation of a Longitudinal, Integrated Curricular Theme and Novel Competency Framework at Harvard Medical School. PLOS Climate, 3, e0000412. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pclm.0000412

Könings, K. D., Mordang, S., Smeenk, F., Stassen, L., & Ramani, S. (2021). Learner Involvement in the Co-Creation of Teaching and Learning: AMEE Guide No. 138. Medical Teacher, 43(8), 924-936. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159x.2020.1838464

Laney, E., Rabin, B., & Philipsborn, R. (2022). Climate Resources for Health Education Implementation Guide: A Co-Creation Model for Students and Educators Implementing and Adapting CRHE Resources. 15. https://climatehealthed.org/wp-content/uploads/2022/05/CRHE-Implementation-Guide_7.30.22.pdf

Liu, I., Rabin, B., Manivannan, M., Laney, E., & Philipsborn, R. (2022). Evaluating Strengths and Opportunities for a Co-Created Climate Change Curriculum: Medical Student Perspectives. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1021125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1021125

Rabin, B. M., Laney, E. B., & Philipsborn, R. P. (2020). The Unique Role of Medical Students in Catalyzing Climate Change Education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 2382120520957653. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520957653

Salas, R. N., & Solomon, C. G. (2019). The Climate Crisis – Health and Care Delivery. The New England Journal of Medicine, 381(8), e13. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1906035

Stoddard, H. A., Lee, A. C., & Gooding, H. C. (2025). Empowerment of Learners through Curriculum Co-Creation: Practical Implications of a Radical Educational Theory. Teaching and Learning in Medicine, 37(2):261-267. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401334.2024.2313212

van Schaik, S. M. (2021). Accessible and Adaptable Faculty Development to Support Curriculum Reform in Medical Education. Academic Medicine, 96(4), 495-500. https://doi.org/10.1097/acm.0000000000003804

Emaline Laney, MD, MSc, MSc

Resident, Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA, elaney@mgb.org

Madhu Manivannan, MD

Resident, Department of Pediatrics, University of California San Francisco Benioff Children’s Hospital, Oakland, CA

Irene Liu Katz, MD, MPH

Department of Anesthesiology and Pain Medicine, University of California, Davis Health, Sacramento, CA

Benjamin Rabin, MD, MPH

Department of Medicine, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

Rebecca Philipsborn, MD, MPA

Associate Professor of Pediatrics, General Pediatrics and Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Emory University School of Medicine and Rollins School of Public Health, ORCID 0000-0002-2843-7509.

Published: 7/21/25