Integrating new topics in health professions education into Observed Structured Clinical Encounters provides a valuable strategy for assessing learners’ knowledge and skills.

ABSTRACT

Extreme heat and higher temperatures driven by climate change have increased the utilization of the emergency department by contributing to a range of illnesses and excess mortality, particularly in urban areas and for vulnerable populations. The Climate Change and Environmental Health thread was formally added to the Emory School of Medicine curriculum in 2022 to address the challenge of educating medical students on the link between climate change and the health of their patients. The formalization of this thread throughout the 4-year curriculum led to new content integration into the clerkship years. The Thread Director, student leadership, Emergency Medicine clerkship leadership, and the School of Medicine Human Simulation Education Center team collaborated to update an existing emergency medicine Observed Structured Clinical Examination to assess learners on their retention and application of climate change and environmental health knowledge and skills related to heat illness. Future work will include a more robust rubric for the assessment and evaluation of the students’ discharge planning counseling.

INTRODUCTION

Extreme heat and higher temperatures driven by climate change contribute to increased utilization of emergency departments, a widening range of illnesses, and excess mortality (Vaidyanathan, Gates, Brown, Prezzato, & Bernstein, 2024). Illnesses directly caused by heat exposure include heat exhaustion, heat stroke, rhabdomyolysis, and hyperthermia (Faurie, Varghese, Liu, & Bi, 2022). Heat exposure can also cause acute worsening of chronic diseases including chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, cardiovascular disease, renal disease, and neurovascular disease as well as contribute to an increased incidence of trauma and violence (Girma, Liu, Schinasi, Clougherty, & Sheffield, 2023; Hayden et al., 2023).

Extreme heat is intensified in urban areas due to the urban heat island effect (Mohajerani, Bakaric, & Jeffrey-Bailey, 2017). Relatively less green space to dissipate heat and relatively more man-made structures that absorb heat contribute to temperatures in cities that are 15-20°F hotter than surrounding neighborhoods (Climate Central, 2021). In fact, since 2000 Atlanta has experienced, on average, a more than doubling of extreme heat days in the summer months, lengthening of heat waves, and an earlier seasonal onset and later seasonal resolution of extreme heat (ARC Research, 2024).

Extreme heat exposure risks further increases for individuals who work or exercise strenuously outdoors as well as those living in neighborhoods with compounding environmental stressors, including a high concentration of heat-absorbing infrastructure, asphalt and industry (Hoffman, Shandas, & Pendleton, 2020). Vulnerability increases for individuals who are unprepared for, unaware of, or unable to access protective measures (e.g., heat action plans, air conditioning, safe housing, hydration breaks) or community resources (e.g., social support systems, cooling centers, energy-assistance programs) for extreme heat events (Derakhshan, Eisenman, Basu, & Longcore, 2024). Physiologically, the risk of harm from extreme heat is amplified for individuals who are very young or very old, pregnant individuals, and those with existing chronic conditions or healthcare needs (Hayden et al., 2023).

Physicians in emergency departments across Atlanta are likely to continue to see an increased frequency and severity of heat-related illnesses. The risks of illness from extreme heat also resonate beyond Atlanta, with 87% of the US population projected to live in cities by 2050 (United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, 2019). With climate change and extreme heat posing a serious and increasing threat to patients, health professional students require training on recognizing, assessing, and addressing illnesses related to extreme heat as well as counseling patients on strategies to prevent harm and reduce risks upon discharge from the emergency department. This climate reality provided an opportunity to develop a curriculum and embed it within an existing required medical school Emergency Medicine (EM) clinical clerkship.

THE THREAD

The Climate Change and Environmental Health (CCEH) thread grew out of a faculty and student partnership to co-create and disseminate CCEH content throughout the pre-clinical phase of the Emory University School of Medicine (EUSOM) curriculum starting in 2020 (Rabin, Laney, & Philipsborn, 2020). Formally added to the medical student curriculum in 2022, the thread aims to prepare students to recognize, assess, address—and ultimately prevent—environmental health challenges faced by patients. The thread educates medical students on ways in which environmental factors, including climate change-driven exposures, influence the pathophysiology of disease as well as patient risk factors, disease courses, and plans of care.

In focus groups conducted to evaluate the pre-clinical CCEH curriculum, students reflected on the integration of heat illness, with one stating, “When they showed the map with the redlining, and how it overlapped perfectly with the map of the high incidence of heat stroke and the ambient temperature being higher, I think that really impacted me” (Liu, Rabin, Manivannan, Laney, & Philipsborn, 2022). Students also requested more emphasis on the application of CCEH content to direct patient care, clinical rotations, and clinical decision-making. While pre-clinical students described climate change as “something that you consider in your daily practice… and hopefully moving forward as a physician” (Liu et al., 2022), the degree to which they retain this perspective and incorporate climate-informed principles into patient care as they advance through clinical clerkships is unknown. In response to student suggestions and following formalization of the thread, the CCEH team began integrating didactic content and formative evaluation into the clerkship years.

THE CLERKSHIP

The EUSOM Emergency Medicine clerkship is a required four-week fourth-year rotation during which medical students synthesize and apply knowledge gained in the first three years of medical school to evaluate and manage undifferentiated patients in the emergency department. While the EM clerkship historically included didactics on environmental emergencies, the EM and CCEH leadership recognized an opportunity to enhance EM-CCEH content related to extreme heat and to leverage existing EM assessment strategies to assess learners’ application of this content. The integration and application of CCEH content in EM builds upon the content covered earlier in the medical school curriculum.

ASSESSMENT GAPS

Even as the CCEH thread continues to weave content throughout the curriculum for medical students, learner assessment strategies have lagged. Learner assessments for the CCEH thread, like CCEH content, are integrated into the pre-clinical course or clinical clerkship in which content is delivered. Most assessment strategies implemented to date are lower on Miller’s Pyramid of clinical skills development (Miller, 1990). For example, Goel et al. discuss assessment strategies in the pre-clinical Pulmonary course that, while well-matched to pre-clinical content, assess learner recall of key content on multiple-choice questions and interpretation and application of key content on a short essay question (Goel, Emanuels, Philipsborn, & Mehta, 2025), but not students’ ability to apply their knowledge in real patient care situations. Overall, the CCEH Thread lacked assessments that required demonstration of knowledge and skills in either the clinical environment or in simulated patient encounters.

This challenge for Emory’s CCEH curriculum reflects a challenge for the field as a whole. While the majority of medical schools now include content on climate change and health in required curricula, data on whether and how students are assessed on this content is lacking. To date, most curriculum publications on climate change employ learner self-assessment, short answer quizzes, and pre- and post-activity assessments. In one exception, educators developed a standardized patient case on wildfire exposure as a risk for asthma exacerbation and implemented it in an observed structured clinical examination (OSCE) in which learners interacted with trained actors known as standardized patients (SPs) (Ramkumar, Rosencranz, & Herzog, 2021). This assessment was part of a single exercise rather than a course, but their experience suggests the feasibility and acceptability of including climate-related risk factors in OSCEs as a tool to assess learner competencies, and by extension, towards ultimately evaluating curricular outcomes.

THE OSCE

At Emory, the CCEH Thread Director, CCEH student leadership, and EM Clerkship leadership agreed that an OSCE would provide an excellent opportunity for assessing students completing the EM clerkship, and that doing so was feasible, as they already employed an evaluation at the conclusion of the clerkship in the form of three SP encounters. One of the case scenarios revolved around a patient who presents to the emergency department with an asthma exacerbation. This case was revised to facilitate assessment of students’ ability to identify the patient’s risk for health harms from climate change and to incorporate components of climate-related health counseling in their approach to standardized patients.

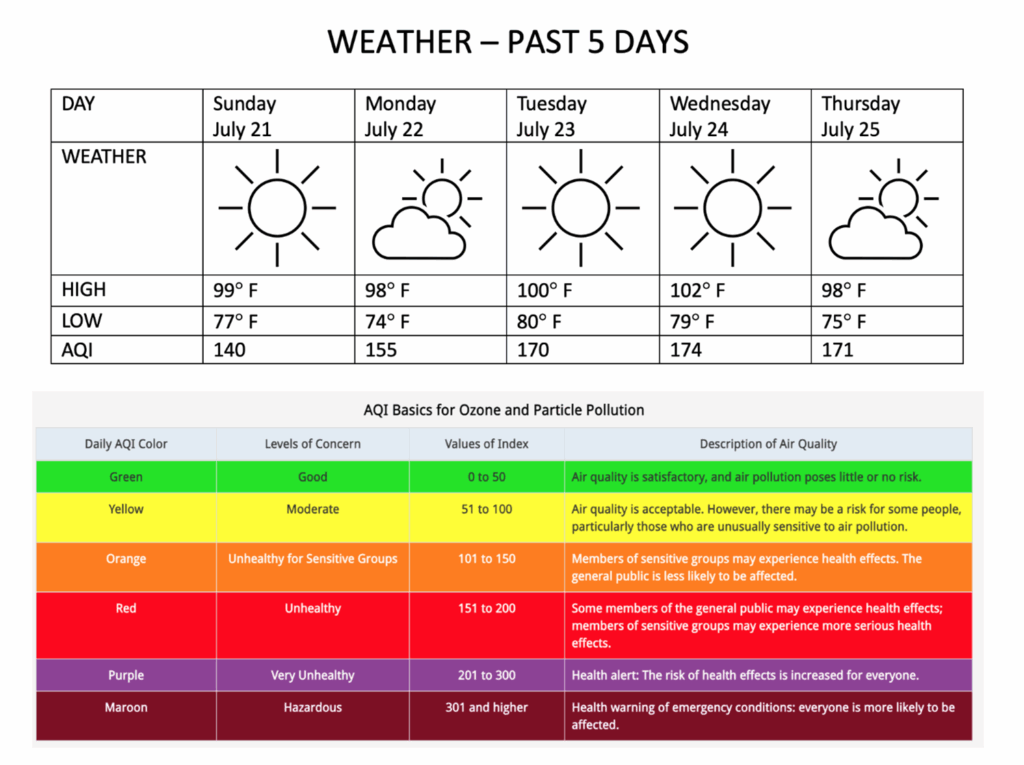

Once goals for the assessment were identified, the team collaborated with the Human Simulation Education Center (HSEC) at EUSOM to hone the case stimulus, which is used to supply students with information required for the case and to develop training materials for the SPs. The case scenario was updated to incorporate CCEH triggers of asthma (in this case, extreme heat and air pollution) in the history of present illness. The simulation is structured to occur in a heat wave, and learners are presented with weather and climate data, including daily temperature minimums and maximums as well as daily maximum air quality indices, for the five days preceding the simulated patient’s presentation to the emergency department (Figure 1).

This depiction of ambient conditions contextualizes the exposure risk for the patient and facilitates assessment of learners’ ability to interpret the local air quality index in the setting of respiratory symptoms. As the standardized patients understood the purpose of adding climate change and socioeconomic factors to the case, they were eager to adopt the changes. The process was easily accomplished, with all parties invested in the change to bring new content to the OSCE.

The updated case stimulus was piloted in April of 2024 and has continued monthly with each new cohort of students on the EM clerkship. In the current iteration of the encounter, weather and air quality information are presented to the students prior to interacting with the standardized patient. This specific attention to the environmental context of the case helps to bridge the potential cognitive dissonance between ambient temperatures in the simulated scenario and ambient temperatures on the day of the OSCE for learners who take the EM clerkship in cooler months. The case is formative, with no grade assigned, eliminating any potential disadvantages for student cohorts related to the seasonality of heat illness and the timing of their EM clerkship.

While we do not have data yet, anecdotally the case has been well-received. Since the CCEH content is integrated into the case, the students’ ability to communicate CCEH information likely influences their overall performance on the case, particularly in communication-related domains.

In the next phase of case development and implementation of this OSCE exercise, we plan to formalize tools to assess student performance. We will update the case’s scoring rubric to include assessment of a student’s ability to take a focused environmental history, to communicate the significance of environmental risk factors for the patient’s presentation and acute illness, and to counsel the standardized patient and provide patient-centered anticipatory guidance at discharge on strategies to prevent future harm. This assessment strategy would connect this OSCE to skills learned in courses prior to emergency medicine while creating a more robust assessment tool for a student’s recognition of the importance of CCEH, ability to elucidate CCEH risks, and ability to integrate knowledge of CCEH into the patient encounter. In providing anticipatory guidance, students can refer to new tools from the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), suggest connecting with social work or other community resources, and leverage the interprofessional care team to ensure their standardized patient’s needs are met (CDC Heat and Health Initiative, 2024). We are also considering implementing a survey tool for standardized patients to assess each student’s ability to provide appropriate discharge counseling for improved patient safety in extreme heat conditions.

REFLECTIONS

In considering our progress to date, we are grateful for the partnership between the CCEH thread and the EM clerkship – the first fourth year clerkship to co-create and integrate this content. Practically speaking, the process of curriculum co-creation for a fourth-year clerkship with students and faculty leadership posed new challenges for the CCEH thread. To maintain the authenticity of the experience for learners and to avoid creating an advantage for students involved in creating the CCEH curriculum, faculty did not include any students who had not yet taken the EM clerkship in the co-creation process. Although there is a relatively limited time between when students take the EM clerkship and when they graduate, students and faculty still partnered in the co-creation that has become the hallmark of the CCEH thread. Interested students identified opportunities for CCEH content and assessment within the existing framework of the EM clerkship and began the process of engaging EM leadership during their clerkship experience. Going forward, EM course representatives, CCEH thread representatives, and Emory Medical Students for Climate Action curriculum chairs can support faculty in interpreting feedback on the OSCE.

The integration of climate content into the OSCE was well received by standardized patients and leaders in our simulation center. It was a seamless addition to our existing OSCE case and didactic sessions on climate change and the risks posed to our patients. For others planning to implement a similar case, we would recommend developing the history more extensively and updating the case rubric to more explicitly assess learner performance on obtaining patient-centered information relevant to health risks from extreme heat and delivering CCEH counseling.

The ambient temperature data component added an interesting dimension of simulation and awareness of patient environmental factors outside of the exam room. For learners taking the EM clerkship in cooler months, the environmental context and ambient temperature exposure risk in the case required suspension of disbelief and full immersion into the simulated environment. Students who do not see heat illness as frequently in the clinical environment during their clerkship arguably have an increased need to practice knowledge and skills that they have obtained throughout the curriculum in the simulated clinical setting. The team implementing the exercise emphasized the unique seasonal considerations of this case to students in a brief orientation to set expectations and minimize confusion. Anecdotally, this framing was well-received by students. Those seeking to implement a similar exercise elsewhere may want to be similarly intentional in setting expectations for this layer of the simulation prior to the exercise.

Since the envisioning of this activity, in April 2024, the CDC released a toolkit for healthcare professionals on heat and health, including clinical guidance, medication risk tables, and heat action plans alongside a HeatRisk Tool that provides easy-to-understand, zip-code specific heat risk and general health guidance (CDC Heat and Health Initiative, 2024). This toolkit is a helpful additional resource for students as they interact with patients. The convergence of the temperature extremes of the climate crisis and new clinical guidance from public health professionals and the CDC underscores the value of leveraging interprofessional partnerships and resources in training learners for climate-related health challenges to support patient health.

In conclusion, collaboration between the EM clerkship and the CCEH thread afforded an opportunity to reinforce content taught in the pre-clinical phase of the curriculum in the clinical learning environment and to assess learners on their retention and application of cumulative CCEH knowledge and skills related to heat illness. Existing OSCEs provide a valuable strategy to integrate assessment of CCEH content in longitudinal curricula into clinical training. In this example, heat and air pollution were incorporated as exposure risks for asthma exacerbation in a simulated emergency department setting. Our pilot to add climate and health to one EM didactic session and to assess learners’ application of this content within the context of an existing EM OSCE case is generalizable to many disease processes and clinical care settings.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Dr. Philipsborn would like to acknowledge support from the Josiah Macy Jr Foundation that has helped to support this work. She also served as an unpaid content reviewer for the CDC HeatRisk Tool. Dr. Philipsborn served as an unpaid subject matter expert for some of the clinical guidance for health professionals and patient toolkits created by CDC’s Heat and Health Initia

Amin, M., Kirkland, O., Ortiz, P., & Waldron, A. (2024, November). Extreme heat and energy challenges in Atlanta: Insight and impacts. Atlanta Regional Commission. https://33n.atlantaregional.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Fellows-Heat-Risk-for-33N-Nov-2024.pdf

CDC Heat and Health Initiative. (2024). CDC Announces Important Advances in Protecting Americans from Heat [Press release]. https://www.cdc.gov/media/releases/2024/p0422-heat-protection.html

Climate Central. (2021). Hot Zones: Urban Heat Islands. Retrieved from https://www.climatecentral.org/climate-matters/urban-heat-islands

Derakhshan, S., Eisenman, D. P., Basu, R., & Longcore, T. (2024). Do social vulnerability indices correlate with extreme heat health outcomes? The Journal of Climate Change and Health, 18, 100276. :https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joclim.2023.100276

Faurie, C., Varghese, B. M., Liu, J., & Bi, P. (2022). Association between high temperature and heatwaves with heat-related illnesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Science of the Total Environment, 852, 158332. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scitotenv.2022.158332

Girma, B., Liu, B., Schinasi, L. H., Clougherty, J. E., & Sheffield, P. E. (2023). High ambient temperatures associations with children and young adult injury emergency department visits in NYC. Environmental Research: Health, 1(3), 035004. https://doi.org/10.1088/2752-5309/ace27b

Goel, R., Emanuels, A., Philipsborn, R., & Mehta, A. J. (2025). Assessing First Year Medical Students‘ Application of Climate Change and Pulmonary Health Knowledge on an End-of-Course Exam. Intersections: The Education Journal of the Woodruff Health Sciences Center. https://doi.org/10.59450/YVDO9824

Hayden, M. H., Schramm, P. J., Beard, C. B., Bell, J. E., Bernstein, A. S., Bieniek-Tobasco, A., . . .& Wilhelmi, O. V. (2023). Human health. In A. R. Crimmins, C. W. Avery, D. R. Easterling, K. E. Kunkel, B. C. Stewart, & T. K. Maycock (Eds.), Fifth National Climate Assessment. U.S. Global Change Research Program.

Hoffman, J. S., Shandas, V., & Pendleton, N. (2020). The Effects of Historical Housing Policies on Resident Exposure to Intra-Urban Heat: a Study of 108 US Urban Areas. Climate, 8(1),12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cli8010012

Liu, I., Rabin, B., Manivannan, M., Laney, E., & Philipsborn, R. (2022). Evaluating strengths and opportunities for a co-created climate change curriculum: Medical student perspectives. Frontiers in Public Health, 10, 1021125. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1021125

Miller, G. E. (1990). The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine, 65(9), S63-67. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045

Mohajerani, A., Bakaric, J., & Jeffrey-Bailey, T. (2017). The urban heat island effect, its causes, and mitigation, with reference to the thermal properties of asphalt concrete. Journal of environmental management, 197, 522-538. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvman.2017.03.095

Rabin, B. M., Laney, E. B., & Philipsborn, R. P. (2020). The Unique Role of Medical Students in Catalyzing Climate Change Education. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 7, 2382120520957653. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120520957653

Ramkumar, J., Rosencranz, H., & Herzog, L. (2021). Asthma Exacerbation Triggered by Wildfire: a Standardized Patient Case to Integrate Climate Change Into Medical Curricula. MedEdPORTAL, 17, 11063. https://doi.org/10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11063

United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. (2018). World urbanization prospects: The 2018 revision. United Nations. https://population.un.org/wup

Vaidyanathan, A. (2024). Heat-related emergency department visits – United States, may-september 2023. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 73. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7315a1

Rebecca Philipsborn, MD

Associate Professor of Pediatrics, General Pediatrics and Gangarosa Department of Environmental Health, Emory University School of Medicine and Rollins School of Public Health, ORCID 0000-0002-2843-7509

Caroline B. Braun, MD

PGY2, Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology, Oregon Health and Sciences University

Daniel Brown, BA

Human Simulation Education Center, Emory University School of Medicine

Steven Lindsey, MD

Assistant Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Assistant Dean for Medical Education, Emory University School of Medicine, ORCID 0000-0002-8944-4585

Megan C. Henn, MD

Associate Professor, Department of Emergency Medicine, Emory University School of Medicine

Published: 7/21/25